The invention of iron made mass-production of weapons possible.

States like Assyria responded by enlarging their armies, putting large numbers of farmers next to the small traditional core of charioteers.

It was impossible to equip all these men with horses, so most fought as infantry.

A combination of heavy and light infantry armed with shields, stabbing and throwing spears

proved very successful against the old chariot elite.

Chariots continued to be used, but their military value was diminished and they kept their position only because cavalry was not fully developed yet.

Enemies like the Arameans adopted this new infantry-dominated style of fighting first and defeated the traditional yearly Assyrian tribute-gathering raids several times.

It was king Tiglath-Pileser III who in the late 8th century BCE reorganized Assyria,

transforming client states into provinces ruled by governors and keeping everything and everybody under tight control.

The Assyrians employed mass deportations, separating subjugated peoples from their leaders, to minimize the chance of revolt.

The old Assyrian army was made up of farmers who took up arms during the campaigning season.

Tiglath-Pileser III diversified this force by creating a true standing army, the "Sab Sharri" (royal army).

Soon there were three categories of soldiers: elite royal guards, long-term professionals and short-term conscripts.

Most men were eligible for service, but this could be either military service or civil, as laborers.

The royal army consisted mostly of chariots, light and heavy cavalry, all composed of native Assyrians.

The auxiliary archers and spearmen were less heavily armored and most came from the ranks of subject peoples.

The army as a whole was heterogeneous, each province supplying a part that had its own language, customs and traditions, both culturally and militarily.

It is unclear if the Assyrians relied mostly on their archers to break up the enemy, or used their heavy spearman in the same role.

Archers as attackers and spearmen as defenders seems the most likely of the two.

Whatever the exact balance, the Neo-Assyrian army was essentially an infantry force, contrasting sharply with the aristocratic chariot armies of the Bronze Age.

Cavalry played a minor role, harassing and sometimes outflanking the enemy and chasing them if they broke.

Early cavalry rode on small horses, had no stirrups or large saddles, so could only wield spears overhand.

Despite the limitations of each troop type, the Assyrian army was a varied force that used combined arms tactics.

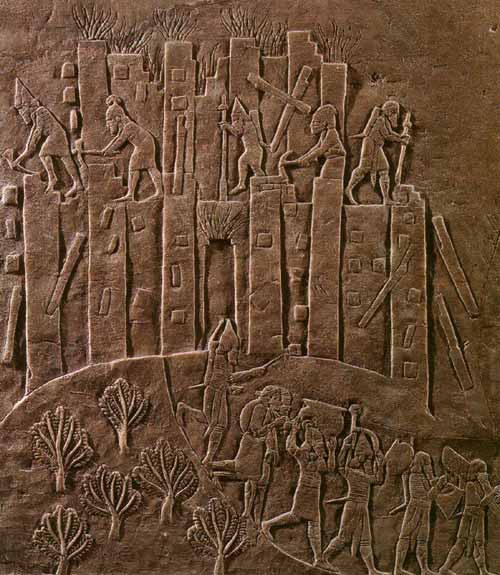

The Assyrian might was so strong that they rarely fought battles; enemies sensibly evaded slaughter and hid behind their city walls.

Therefore the Assyrians frequently had to lay siege and in due course developed advanced siege tactics,

using sappers, scaling ladders,

battering rams and siege towers.

Assyria was a true warrior state, where the king had to personally lead the army to show his skill and bravery.

Lesser heroes were also celebrated, both in Assyria and among their enemies.

This militarism eventually proved their downfall, when the empire descended into civil wars between various provinces and leaders,

which were fought in the martial tradition that the state had developed in the centuries before.

War Matrix - Neo-Assyrian army

Iron Age 1100 BCE - 550 BCE, Armies and troops